The Top Line

The Patent Appeal Board in Canada issued a landmark decision, holding that an AI system is not a valid “inventor” under Canadian patent law. In the result, the patent filed by computer scientist Stephen Thaler and invented by his AI system named “DABUS”, was rejected for failing to meet the requirements to name a proper inventor and for lack of entitlement to file a patent given the lack of any assignment from a valid inventor. The PAB decision is not binding law but will likely be followed by patent examiners in Canada.

On June 5, 2025, the Patent Appeal Board (PAB) at the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) decided against computer scientist Stephen Thaler in his long-running campaign to secure patent rights for inventions generated by his AI system. This marked the latest worldwide chapter, and the first decision in Canada, to determine whether artificial intelligence can be named as an inventor on a patent application. According to the Patent Appeal Board in Thaler, Stephen L. (Re), 2025 CACP 8, the answer is a resounding “no”. Under Canadian law, only humans can be inventors.

Background

The Thaler case deals with one of the most prominent and controversial legal issues at the intersection of AI and intellectual property law – whether an AI system can be recognized as an “inventor” under existing patent regimes.

The patent application at issue is part of a family of patents filed worldwide by computer scientist Stephen Thaler, who developed an artificial intelligence system named the “Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience” (DABUS) in the early-to-mid-2010s. Thaler claimed that DABUS was designed to generate novel inventions without any direct human input or intervention.

DABUS and AI Inventorship Worldwide

Thaler filed patent applications around the world naming DABUS as the sole inventor and himself as the legal representative (or owner by assignment, where it was not possible to designate a legal representative). These applications were clearly designed to test the boundaries of patent law and spark legal and policy debate around AI-generated inventions.

In response, courts and patent offices around the world issued a wave of decisions, the majority firmly rejecting the notion that an AI can be recognized as a named inventor:

- United States: The USPTO, District Courts, and the Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit all said an inventor must be a natural person.

- UK: The UK Supreme Court unanimously held in 2023 that under the UK Patents Act, only a (human) person can be an inventor.

- European Patent Office (EPO): Rejected the application on similar grounds.

- South Africa: Uniquely compared to other jurisdictions, the patent was granted, although it seems that this was only because South Africa lacks a substantive examination system.

- Australia: Initially accepted, but that decision was overturned on appeal.

DABUS in Canada

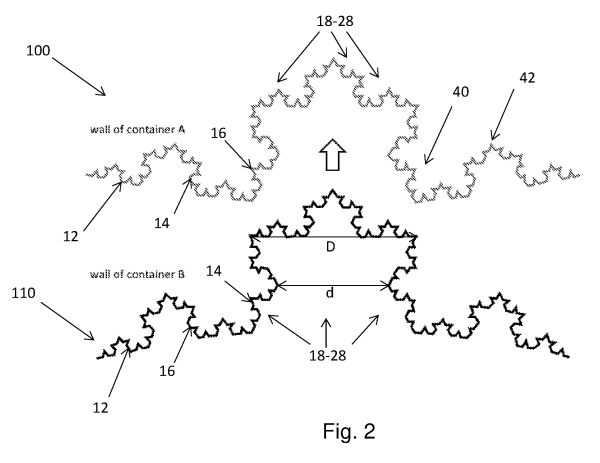

Canadian patent application 3,137,161, filed as an international PCT application on September 17, 2019, named DABUS as the sole inventor. Although it was contained in a single patent application, there were apparently two distinct inventions claimed: a fractal-based food container (Claims 1–9) and a flashing emergency beacon (Claims 10–20).\

(Claim) 1. A food or beverage (10) container comprising:

- a generally cylindrical wall (12) defining an internal chamber of the container, the wall having interior (16) and exterior (14) surfaces and being of uniform thickness;

- a top and a base either end of the generally cylindrical wall;

- wherein the wall (12) has a fractal profile with corresponding convex and concave fractal elements (18-28) on corresponding ones of the interior and exterior surfaces(14, 16);

- wherein the convex and concave fractal elements form pits (40) and bulges (42) in the profile of the wall (12);

- wherein the wall of the container is flexible, permitting flexing of the fractal profile thereof;

- the fractal profile of the wall permits coupling by inter-engagement of a plurality of said containers together; and

- the flexibility of the wall permits disengagement of said or any coupling of a plurality of said containers.

(Claim) 10. A device (2) for attracting enhanced attention, the device comprising:

- (a) an input signal of a lacunar pulse train having characteristics of a pulse frequency of approximately four Hertz and a pulse-train fractal dimension of approximately one-half generated from a random walk over successive 300 millisecond intervals, each step being of equal magnitude and representative of a pulse train satisfying a fractal dimension equation of ln(number of intercepts of a neuron’s net input with a firing threshold)/ln(the total number of 300 ms intervals sampled); and

- (b) at least one controllable light source (6) configured to be pulsatingly operated by said input signal;

- wherein a neural flame is emitted from said at least one controllable light source as a result of said lacunar pulse train.

In November 2021, the patent examiner at CIPO rejected the application on the basis that Canadian patent law requires inventors to be natural persons, disqualifying DABUS. The Commissioner found the application failed to comply with subsection 27(2) of the Patent Act and section 54(1) of the Patent Rules, which require a named inventor and a valid statement of entitlement.

In response, Thaler submitted an affidavit in mid-2022 asserting that, as the owner of DABUS, he was its legal representative and entitled to apply. He also argued that recognizing AI inventors would better reflect modern technological realities and public policy goals. This set the stage for a potential debate on the law and policy rationales behind the “inventorship” in general and the extent to which AI could be involved in an “invention”.

PAB’s Decision

The matter was referred to the Patent Appeal Board in 2024 to determine whether an AI system could legally be considered an inventor. In a preliminary opinion issued that November, the Board affirmed that inventorship under Canadian law is limited to natural persons and that AI cannot assign or hold rights, leaving Thaler’s application non-compliant. Following an oral hearing in February 2025, the Board issued its final decision in June 2025, definitively rejecting AI inventorship under current law.

At the PAB, Thaler raised a plethora of arguments, both legal and philosophical, but the Board held firm and grounded its conclusion that an inventor must be a natural person.

The bulk of the PAB decision focused on defining the word “inventor” (French inventeur) under the Patent Act and Patent Rules including on the textual, contextual, and purposive analysis using well established principles of statutory interpretation.

The PAB acknowledged that the term “inventor” is not defined in the Patent Act (and indeed, acknowledged that the statute does not exclude AI expressly), but held that dictionary definitions, legal precedent, and statutory context all point to the requirement that an “inventor” must be a human being.

On the textual interpretation, the Board rejected Thaler’s definitional analogies. For example, Thaler argued that the meaning of the English words “calculator” and “computer” as set out in dictionaries originally referred to “a person who operates a calculator” and “human computers” – in other words, referring to a human actor – but later evolved, upon the advent of the electronic age, to refer primarily to the machines or devices that performed calculations or computation. These arguments were met with skepticism by PAB, which noted that the term “inventor” (whether in grammatical and ordinary meaning or under the legislative context) has not evolved to include machines.

On contextual and purposive interpretation, Thaler argued for a “broad” interpretation under the Patent Act, citing Amazon.com, 2010 FC 1011 for the idea that the legislation “is not static” and “must be applied in ways that recognize changes in technology”. (This argument hinted at the idea of “technological neutrality” previously discussed in the Supreme Court, although this specific principle was not raised as an argument in the PAB Decision.)

The Board disagreed with the application of a broad interpretation to the word “inventor”, noting that many of the court decisions referring to an expansive interpretation referred to “what” should be patented rather than “who” should be permitted to obtain a patent. (Incidentally, the Supreme Court is expected to hear an appeal on subject-matter eligibility in the fall.) In PAB’s view, expanding the scope of “inventor” to include an AI system would be a technological evolution beyond what was envisioned by the legislators.

Focusing on the context of the legislation under the Patent Act, the PAB detailed numerous instances where the word “inventor” connotes or implies a natural person, rather than a legal person (e.g. corporation) or even an AI system like DABUS. The Board even pointed out various human-centric provisions in the Rules, noting the resulting absurdity of requiring a robot’s name and postal address if “inventor” included AI systems.

Likewise, PAB noted that Canadian courts have consistently treated inventors as “natural persons”, with no precedent for recognizing machines. However, the Board acknowledged that existing precedents were concerned with excluding legal persons (corporations) from the definition of “inventor” rather than the application to artificial intelligence.

The Board also rejected Thaler’s broader policy arguments that denying AI inventorship stifles innovation, noting that Parliament can change the law if it intended to include AI as inventors. The Board also considered that the structure of the patent system itself assumes a human actor in the quid pro quo underlying the patent system – disclosure in exchange for exclusive rights – which AI, lacking personhood, cannot participate in.

On the issue of ownership and entitlement, the Board mostly dodged a slightly different question on whether Thaler could be the appropriate owner of the patent or the legal representative for DABUS. The Board noted that, since DABUS was not a valid “inventor”, there could be no valid legal representative or assignment of ownership, without substantively addressing the question of whether an AI or its output could be “owned” or “assigned”.

However, the Board did address some of the many arguments raised by Thaler on the idea of how an intangible asset can create assignable output. Nonetheless, Thaler’s efforts to equate DABUS to a human employee, profit-generating assets, or even invoking the ancient Roman property law of accession (arguing that if you own a machine, you own its output) were dismissed as inapplicable to modern IP.

Impact on Patent Policy

The PAB ruling aligns Canada with other jurisdictions like the US and UK in affirming that, without legislative reform, only humans can be inventors under current patent law. However, this may not be final word. Thaler has a right of appeal to the Federal Court from the PAB decision, and if other jurisdictions are any guide, he may yet choose to take this case further. Until the court or Parliament weighs in, this decision will be the leading case establishing that AI systems cannot be inventors.

In the US, the United States Patent and Trademark Office has issued guidance papers on the question of whether generative AI can be an inventor (the short answer is: no). To date, there has not yet been any official policy guidance from CIPO’s patent branch. In the realm of copyright, however, CIPO is in the midst of consultation to develop a policy for treatment of generative AI as an “author” and on content ownership issues raised by the use of large language models (LLMs). While the Thaler decision is not official patent office policy, in general it will be binding or influential on patent examiners – practitioners and clients should take note of the impact of this decision in patent prosecution.

It should be noted, however, that the PAB decision did not address other questions related to the intersection of AI and inventorship. For example, the Board did not say much about circumstances where an AI system is used as part of the inventive process (presumably, an AI system cannot be a “co-inventor” under this ruling, but nothing seems to preclude the use of generative AI in the course of generating an invention). Nor did the Board give much guidance on what is required in terms of contribution of “inventiveness” or to the “inventive concept” in respect of human versus AI. These interesting questions may remain to be addressed in the near future.