The Top Line

Lululemon Athletica recently filed a lawsuit against Costco Wholesale in the US, alleging extensive intellectual property infringement involving trademarks, trade dress, and design patents. The complaint accuses Costco of selling lower-priced “dupe” apparel that closely imitates Lululemon’s distinctive SCUBA® hoodies, DEFINE® jackets, and ABC® pants, thereby misappropriating protected visual designs and brand identifiers. As “dupes” gain popularity online, courts may have to decide where the line is between design inspiration and infringement.

Dupes have taken over the fashion world – they are stylish, affordable, and could let people get the “look” of high-end brands without spending a fortune. But while scoring a great “Lulu lookalike” might seem like a win, there’s a legal side to the story that’s easy to overlook. Lululemon’s new lawsuit against Costco is a reminder that when dupes get a little too close, they can cross the line into trademark and design patent infringement.

In this post, we’re taking a brief look at Lululemon’s lawsuit and compare how the U.S. and Canadian legal systems treat design and trade dress infringement.

What Are Design Patents?

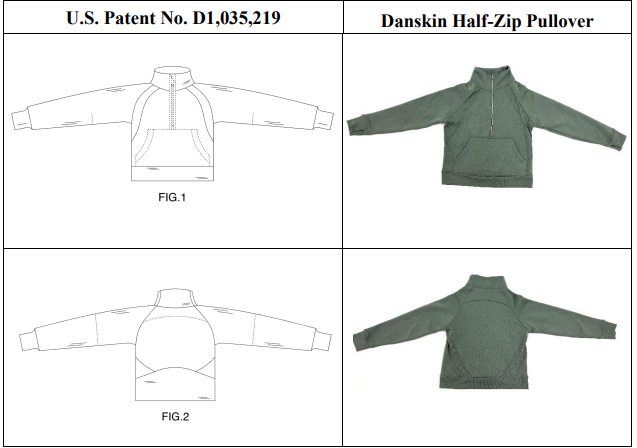

Lululemon is asserting infringement of two US design patents that cover the ornamental design of its SCUBA® hoodies and sweatshirts.

This case involves “design patents“, which are the lesser known cousin of “utility patents”. Generally, design patents protect the visual design of a product rather than its functionality. In the United States, a utility patent protects how an article works and is used, under 35 U.S.C. §101. A design patent, governed by 35 U.S.C. §171, protects the ornamental appearance of a functional item.

In Canada, the equivalent to a U.S. design patent is called an industrial design, which is governed by the Industrial Designs Act. An industrial design generally only covers an ornamental aspect that visually appeals to the consumer. A purely functional item isn’t eligible for design registration if it lacks decorative or aesthetic value.

Industrial design infringement in Canada is judged primarily by visual impression, that is, whether the alleged infringing design appeals to the eye in a way that is confusingly similar to the registered design. Recently, courts have used a four-part analysis focused on prior designs, functional aspects, the scope of the registered design, and a side-by-side comparison from the perspective of an “informed consumer” (someone familiar with the market and context of the product). Importantly, a defendant’s intent, or the fact that their design is also registered, does not shield them from liability. Courts focus on the substance and visual distinctiveness of the designs, not on the motive or process behind them.

Canada does have a registration system for industrial designs, although there are less formalities and less substantive examination compared to the U.S. registration system for design patents. For fashion brands, navigating both legal frameworks is critical to enforcing rights across borders, particularly when visual design is central to brand identity.

Trade Dress: Visual Branding Without a Logo

Lululemon is also asserting trade dress infringement, claiming that Costco copied the distinctive visual appearance of Lululemon’s apparel even when no brand name was used. Three product lines are specifically named in the lawsuit:

- DEFINE® Jacket Trade Dress: Defined by ornamental, non-functional curvilinear seam lines on the front and back.

- SCUBA® Hoodie Trade Dress: Recognizable through unique pocket designs and seam patterns extending from the neckline.

- ABC® Pant Trade Dress: Featuring intricate ornamental lines around the crotch, waistband, and legs that form a distinctive silhouette.

In both the United States and Canada, trade dress plays a key role in protecting the visual identity of a product, but the legal frameworks differ in scope and application. In the U.S., trade dress is explicitly protected under the Lanham Act, where both the packaging of a product and the configuration of the product itself can function as source identifiers, much like traditional trademarks. These trade dress rights may be registered, but protection is also available without registration under 15 U.S.C. §1125(a), so long as the trade dress has acquired distinctiveness and is non-functional.

Canada, by contrast, does not have a statutory definition of “trade dress,” and the concept has evolved through case law under the umbrella of distinctive non-traditional trademarks. Canadian trade dress protection can extend to features such as the shape, packaging, colour, and even store layout or building design, but only if the applicant can establish sufficient consumer recognition (reputation) and distinctiveness in those features.

This difference in legal structure may be particularly relevant to Lululemon’s claims against Costco in a hypothetical case in Canada. In the U.S., Lululemon is asserting trade dress rights over the appearance of its products, like the stitching, seam placement, and pocket shapes of its SCUBA® and DEFINE® apparel, based on their distinctiveness and source-identifying function. The same elements may be protected in Canada under common law and registered trademark rights if the rightsholder can show that consumers associate those design elements with its brand. Ultimately, both systems offer pathways to protect visual branding, but the U.S. provides a more direct statutory route, whereas Canada relies more heavily on demonstrating reputation and distinctiveness within the marketplace.

Trademark Infringement: Confusing Consumers?

In addition to design-based claims, Lululemon accuses Costco of trademark infringement. The trademarks at issue include:

- SCUBA® : Registered for hooded sweatshirts, jackets, and tops. Lululemon alleges Costco used the term or confusingly similar marks on products like the Hi-Tec Men’s Scuba Full Zip, misleading consumers into believing there is an affiliation.

- TIDEWATER TEAL™: A color mark used extensively by Lululemon since 2019 across its popular product lines. The brand claims Costco used the same color name for Danskin hoodies and pullovers, even though “Tidewater Teal” has become closely associated with Lululemon through marketing, customer recognition, and search engine dominance.

In the U.S., trademark law is governed federally by the Lanham Act, which protects the owner’s exclusive right to use a mark when another’s use is likely to cause consumer confusion about the source of goods or services. To win an infringement claim, a plaintiff must prove ownership of a valid mark, that the defendant used a similar mark in commerce without consent, and that the defendant’s use is likely to confuse consumers. U.S. courts often focus on factors such as the strength of the mark, similarity between the marks, actual consumer confusion, and intent.

Canada’s approach under the Trademarks Act similarly grants exclusive rights to registered trademark owners and generally presumes a registration is valid unless challenged. Canadian law also prohibits use of confusingly similar marks and extends protection against depreciation of goodwill, even without consumer confusion. Unlike the U.S., Canadian law has some limited exceptions such as use in personal names or geographic terms, that do not amount to infringement. The scope of protection is tied to the specific goods or services registered. Canadian courts assess confusion as of the hearing date and consider the extent of recognition and goodwill associated with the mark, even when fame is not a prerequisite.

In this case, these differences play out in how claims of confusing lookalike “dupes” are handled. While U.S. law requires showing a likelihood of consumer confusion linked to use in commerce, Canadian law also emphasizes preventing harm to goodwill and brand value beyond direct confusion. Both systems impose liability on corporate officers if they knowingly authorize infringement.

What the Lululemon vs. Costco Lawsuit Means for IP Protection in Fashion

This case demonstrates the growing tension between brand protection and the widespread retail practice of offering lower-priced alternatives or “dupes.” For Lululemon, the complaint is not simply about copycat fashion—it’s about protecting the substantial investment in product design, brand equity, and consumer trust that its trademarks and patents represent.

For retailers, the message is clear: while it’s tempting to catch the latest fashion trend, replicating the look, feel, or name of a popular product – even without using logos – might still land them in legal trouble if it crosses the line into intellectual property infringement.

As this legal battle progresses, it could set key precedents for how aggressively fashion brands can assert their IP rights in the face of growing competition and imitation in the market.

Disclaimer: This post is intended as timely legal commentary and should not be taken as legal opinion or advice. If you have a question about trademarks or industrial designs, please contact a member of our Trademarks Team.